The

Joseph A. Caulder Collection

Past Rotary International Director 1928-29

- Regina, Sask., Canada

"Eyewitness to Rotary International's First 50 Years"

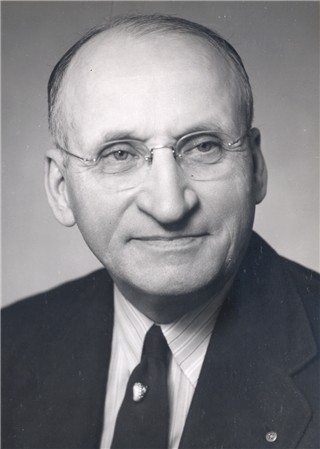

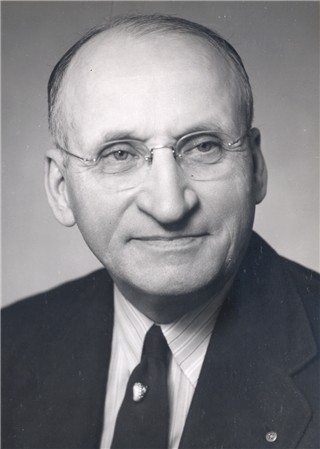

JOSEPH A. CAULDER - An eyewitness to Rotary International's first 50 years.

Album 2 - Page 66, Edgar F. "Daddy" Allen

|

Internal Links

|

Edgar F. "Daddy" Allen Founder, International Society for Crippled Children

Joe Caulder Remembers "Daddy" Allen as everyone called him was from Elyria, Ohio. It can be said that, almost single handed, he built "The International Society for Crippled Children". I met him at one or two Conventions and also at his own club in Elyria and one special night at Butler, Pa., where I was the speaker. Also, we had some friends and business connections at Elyria and I called on "Daddy Allen" whenever I had a chance. No finer Rotarian ever lived. J.A.C.

So We Call Him "DADDY" ALLEN. Tragedy opened a path of service for this Rotarian who fathered a world society to aid all crippled children

By - Paul H. King, President The International Society for the Welfare of Cripples.. On the evening of Memorial Day, 1907, in Elyria, Ohio, two interurban cars telescoped. Eighty-four persons returning home from an outing were killed or injured. Such a tragedy would stir any community, but Elyria folk were unusually aroused. Of the 16 who died of injuries, several might have lived had there been a general hospital in the town. A local sanitarium proved inadequate. One of the victims was Homer, 18 year old son of Mr. and Mrs. Edgar F. Allen. Homer was one of those who might have lived, they were told, if he only could have been rushed to a hospital. The Allens were shocked, dazed, then slowly set themselves to carry on - hiding the void in their hearts. Allen had his work to do. That helped - some. One morning on the way to his tie and telegraph-pole plant, he met an old lawyer friend. They talked of commonplaces; then, as they were about to part, the friend asked: "Have you collected damages for your son's death?" "Have I collected?" Allen stopped, his face working; "Accept money for my son's death?" But his friend had a suggestion. "Why not accept the money and with it start a modern hospital?" Indeed, why not? Allen asked himself that many times. The suggestion was discussed in the Allen home, and approved. Then he went to work on it. On October 30,1908, The Elyria Memorial Hospital was dedicated, with Edgar F. Allen its unsalaried treasurer. He had previously sold his business to devote all his time to the hospital project. Today there are five buildings in the hospital plant - a million dollar community service center. But that is a middle-of-the-book chapter in the career of the man who, wherever the plea of crippled children is heeded the world over, came to be known as "Daddy" Allen. Let us return to th first chapter and speak of a tot by the name of Jimmy. A bout with infantile paralysis brought Jimmy to the hospital in 1911. Daddy Allen was attracted to his cheerful freckled face. Often on his rounds he talked to Jimmy, and watched with pride his steady improvement. Then he wondered if there were other Jimmies about who needed help. There were - 200 of them in his own Lorain County! "Why shouldn't there be a hospital for crippled children?" he demanded of a friendly medico. "There should be," he answered himself, and the doctor agreed. They began at once to do something about it. Among others they interested Mrs. Ada Gates, widow of a Cleveland advertising executive. On April 6, 1915, the Gates Memorial Hospital for Crippled Children was dedicated. And from then on the cause of the crippled child became Edgar F. Allen's magnificent obsession. "We expected that crippled children would pour in from all over Ohio after the Gates Hospital was opened," Daddy Allen once told me, "but much to our surprise this happened neither the first nor the second year." The psychology of the cripple and his parents hadn't been considered. Many could not afford care, for example, but were too proud to accept "charity." Eventually the whole problem of the handicapped was found to be a matter of, first, social welfare; second, public health; third, education; and fourth, employment. That analysis holds as good today as when Daddy Allen first charted it many years ago. Investigation convinced him that in the care of cripples the State should be concerned. So he sought a "constituency" for crippled children. He talked to branches of the Y.M.C.A., churches, and chambers of commerce. In 1919, after three years of effort, he organized the Ohio Society for Crippled Children. Membership was recruited from the Rotary Clubs of Elyria, Toledo, and Cleveland - for among his fellow Rotarians Daddy found ready ears, warm hearts, and willing hands. It is, in passing, a matter of interest that Rotarians of Syracuse, New York, were sponsoring crippled-children work as early as 1913! By 1921, Daddy's Ohio Society had gained sufficient momentum to enlist the aid of the Ohio Hospital Association; the State Departments of Health, Welfare, and Education; and the orthopedic surgeons of the State. Cemented by Daddy's energy, the "0hio plan" for corrective care and education soon secured legislative support, and became a functioning reality. But Daddy Allen didn't hang up his spurs. He was just beginning. He saw too much work undone, and adopted "Keep on keeping on" as his motto. Rotarians in other States had heard of his work, and he was in demand as a luncheon speaker. It was at Port Huron, Michigan, Rotary luncheon that I first saw and met Daddy Allen. At first he seemed to be just an ordinary businessman talking about his hobby - crippled children - before a Club which was already maintaining an excellent camp for cripples. But there was something about Daddy that made him different; his earnestness! I had never been especially interested in crippled children, but that day changed my life, just as the death of his son and tiny Jimmy's miraculous recovery had changed Daddy Allen's. I had no idea, of course, that. I was to take over his work when he could no longer carry on, and that, "as one of his boys", I was to succeed him as president of his International Society for Crippled Children. This rather short, bald, smiling fellow who talked at luncheon that day in Port Huron wasn't what the world calls a genius. It would be more apt to say that he was just a run-of-the-mill businessman. He was modest, conservative, popular with men and youngsters, with a great heart and a marvelous singleness of purpose. He became the very embodiment of St. Paul's word: "This one thing I do." And he did it with all his might. Yes, it was his magnificent obsession. When I became his "right-hand man," as first Vice-President of the Society, he would often say to me: "Paul, don't load up with so many of these other things. You'll have more time for crippled children." Nothing else seemed important. At times he even lost a bit of patience with those who couldn't go all the way with him. But when he needed money, Daddy Allen always got it. He'd strike out for a town, and go down one side of the street and up the other. And he's always come home with cash when the Society needed it most! Daddy Allen not only knew but mixed with people, young and old. I remember well a visit we made at a school for cripples in Washington, D.C. Ushered into a room, we faced 40 or 50 youngsters. Always at his ease, Daddy Allen just smiled and started making shadow pictures of rabbits, dogs, and ducks upon a wall. In a few moments the little folks were giggling and in love with him. His words of encouragement fell upon eager ears, and many a youngster there and elsewhere found his place in life through visits of this kind. The same was true with hard-boiled bankers - this disarming manner of Daddy Allen's. His dynamic personality and his enthusiasm always softened them and his work went ahead. He never begged. His point was that it was a privilege to help youngsters with crooked spines or twisted legs. He was a prolific letter writer and traveler, covering as much as 40,000 miles in a year, exclusive of European jaunts. No one was too important for him to see: Presidents, Governors, and Princes. Once when the Society was badly in need of funds, I proposed, as chairman of the finance committee, that we sell crippled-children seals. "A good idea, Paul," he beamed; "go and get President Roosevelt to endorse the plan." It was as simple as that with him. I went to see the President, who gave us a splendid letter approving the seals, which were adopted at the Society's Wichita, Kansas, convention in 1933. Now each year finds them on sale and in ever-increasing demand at Easter time. And no one was too unimportant, either Daddy wrote and called on the humblest. He didn't feel that he needed "the biggest men," or that he needed thousands of supports to do things. Small groups with enthusiasm were enough. And he'd rather have a man give service than money. He saw in Rotary a great force to advance the movement. On October 13,1921, Daddy Allen called together at Toledo, Ohio, approximately 100 Rotarians and other professional people from Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, New York, and Ontario, Canada. That the representation from outside the United States was limited didn't daunt Daddy Allen. It still became an International Society, and he became its first President. Our beloved Founder of Rotary was there. A warm friend of Edgar Allen, Paul Harris' wise counsel and able support have meant much to the cause. Last year from July 16 to 22, in the city of London, England, that same Society saw 420 delegates from 45 countries assembled in its fourth world congress. Its constituent in the United States, the National Society, works with the Children's Bureau of the Department of Labor and Rehabilitation Division of the Office of Education in the Department of the Interior, and many State agencies; it co-operates with Rotarians, Shriners, Kiwanians, Elks, Parent-Teacher Associations, the American Legion, members of the Federation of Women's Clubs, and other organizations. How the work of Daddy Allen spread to other countries is a story in itself. Typical was the influence of the Crippled Children Assembly at Rotary's 1933 Convention in Boston. Among those attending an Assembly breakfast was the then District Governor Thomas List, of New Zealand. Seeing Tom's interest, I invited him to the speakers' t able "to say a few words." "If you fellows can do this sort of thing, why can't we?" he asked in the course of his short speech. He answered his own question by going home and organizing the New Zealand Society for Cripples. Lord Nuffield became interested in the program, and this English industrialist gave £50,000. .A man and wife in Auckland donated a house and 13 acres to be used as a home for cripples, and Lord Nuffield came along with £10,000 as an endowment for such homes. Mexico is another example. Following Rotary's Convention and its Crippled Children Assembly at Mexico City in 1935, the Mexican Association of Friends of Crippled Children was formed. Ten years earlier, in 1935, two Rotarians from Dublin found a seed which they planted back home. Soon all of Ireland blossomed with work in behalf of cripples. One could mention other examples. Enthusiasm for Daddy Allen's vision resulted in four great world congresses, which grew out of Rotary's 1927 Convention in Ostend, Belgium Geneva, The Hague, Budapest, and London. At the Geneva congress it was suggested that each delegation contribute $100 as the membership fee. Daddy Allen arose and said: "I don't think these people have come prepared to pay a fee of this kind. I suggest you just forget about it, and let me take care of the fees." And he did. At that same meeting there were 11 German delegates who couldn't speak a word of English, and one who knew a little of the language. Daddy Allen so impressed the group that they asked the 12th delegate to teach them Daddy's name and several other English words for a surprise at the final session. As the congress ended, these delegates stood in a group, and said farewell in voices choked with emotion: "Good-by, dear Daddy Allen!" These were the only words of English they knew - words which thousands of children have used in hospital wards in hundreds of cities. It was a beautiful and touching climax to an eventful conclave. It has been said that behind every good man is a good woman, and such is true of "Mother" Allen. Constantly with her husband, she shared his views and his problems. It was she who did so much to encourage and support him in his humanitarian work. And while Daddy .Allen lost one of his two sons in the tragedy which became the foundation of his work, his other son, Frank B. Allen, has become a part of the Allen tradition. He is now president of the Pennsylvania Society for Crippled Children. Daddy Allen is dead - but he still lives. A heart ailment forced retirement upon him six year ago, when he became president emeritus of the Ohio and the International Societies. Daddy died on September 20, 1937, but his work goes on - far beyond his dreams, ever developing, ever advancing, but not yet done. Occasionally, however, some well-meaning Rotarian not fully conversant with the situation will be misled by the fact that governmental agencies are collaborating. "Now that the Government has taken over crippled-children work," a delegate at a recent District Conference said, "or Club has taken up other Activities." No man was ever so wrong. The work for crippled children is but well started. The more agencies and the greater governmental interest, the better. Governmental support is fine, but it can never take the place of the heart interest of the volunteer worker, both in and out of Rotary. Each is essential to a well-balanced and successful program. With possibly 6 million cripples in the world there is plenty of work for every man of us. When every crippled child has been cared for, treated, and cured, if possible; when every crippled child is educated, trained, and given a place in the world; when the causes of crippling are eradicated and crippling is prevented - then will our work be done, and not until. Sometimes the way is difficult, sometimes the progress seems slow, sometimes the task appears too great, but no matter how hard the going gets, Daddy Allen's slogan still rings true: "Keep on keeping on." From - The Rotarian, November 1940. [Reprinted by Permission]

|

| Copyright© Daniel W. Mooers |

Rotary® and Rotary International® are registered trademarks of Rotary International Webmaster: dwm@mooers-law.com |