The

Joseph A. Caulder Collection

Past Rotary International Director 1928-29

- Regina, Sask., Canada

"Eyewitness to Rotary International's First 50 Years"

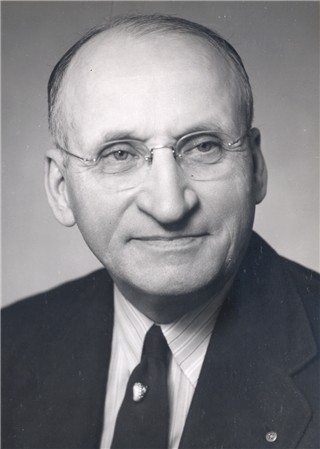

JOSEPH A. CAULDER - An eyewitness to Rotary International's first 50 years.

Album 1, Page 2 - Article by Harry Ruggles

|

Internal Links

|

SO I SAID: "LET'S SING!" From-The Rotarian, February 1952 By Harry L. Ruggles - as Told to Leland D. Case. Something's happened - something to put the tingle in the veins of a man 80 years old! Here my Josephine and I have been living quietly in Beverly Hills like thousands of other retired couples spending sunset years in California. Then suddenly comes a command - that's what they called it - for me to go back to Chicago to be honored guest of the Rotary Club I helped Paul Harris get going back in 1905. And now I'm asked for reminiscences of those days by The Rotarian. Well, I can't turn down The Rotarian either. You see, I was on hand when it was born too. That was in 1911. Paul Harris was eager to have more Rotary Clubs and thought it would be helpful to circulate a long article he'd written about Rational Rotarianism. Chesley R. Perry was Secretary of the National Association of Rotary Clubs - now Rotary International - and grabbed the idea. He'd make Paul's article into Volume 1, Number 1, of a regular publication. Ches didn't have any money for it - but that didn't stop Ches. He got advertisements and persuaded me to print The National Rotarian. It was a flimsy little thing - tabloid size and 12 pages. Only Paul and Ches could have foreseen The Rotarian of today coming from it. But thatís the sort of men they were. They remind me of a phrase Iíve heard my father read from the Bible many times at our morning family altar at our old home in Decatur, Michigan. It's this: ". . . your young men shall see visions." Paul was a man with a vision. I first met him when he came into my print shop one day with a copy for a letterhead. Paul was a good-looking young fellow - mustache and all - who was just beginning to dig in his toes as a lawyer. Much of his practice was handling bad debts for doctors. In fact, collecting an I.O.U. led directly to starting the world's first Rotary Club. Here's the story: One day Paul had business in a Chicago South Side coal office. As he passed a desk near the door, a young chap introduced himself as Silvester Schiele. "I loaned $20 to a friend several months ago," he said, "and when I asked him recently to pay up, he told me, "Try to get it!" Could you help me?" Paul took the I.O.U. and was back in a few days with the 20 bucks. That little incident is worth remembering, I think, because in it is the nubbin of what started Rotary. It's simply that business is honorable and that through it one can and usually does find friends. Collecting that I.O.U. brought Paul and Silvester together They liked each other - and did for the rest of their long lives. When Paul got the idea for "a new club," he naturally talked to Silvester about it first - and Silvester became its first President. What made Paul's club unlike all others at the very start was that instead of drawing together like-minded men - all lawyers, all doctors, and so on - it took men from different lines. That set the pattern for Rotary's "classification principle," still followed. Paul's idea was that it would be natural for noncompetitors to get acquainted easily and then swap business, but we soon had rules to make sure they did. Getting new customers was important to us young fellows struggling to get ahead in a big city! I used to lure new prospects by telling them "we're one for all and all for one" - and, "being a member is like having, say, 25 salesmen out working for you." I'd point to my new printing accounts or to the estate business turned over to our lawyer member, Paul Harris, by Barney Arntzen, the undertaker. Why, we even had a "statistician" to keep tab on business given and received among members. That position was abolished after about five years, but as late as 1910 when a bunch of us Chicago Rotarians paid our way to Minneapolis and St. Paul to organize Clubs, we stressed the profit angle. I doubt if we'd have got started without it. Exchange of business was, in a way, selfish. That's what critics tell us. But I think they skip a point very important to us in those days. It is that, although we ourselves expected to profit from business exchange, we felt good way down inside because we were helping the other fellow by bringing him new customers. We even had a Committee for the job. Any Rotarian "in Dutch" with his creditors, or even his wife, could go to it for advice. Often advice was all that he needed. If he was short on capital, we'd get a loan from Rufus ("Rough House") Chapin's bank, various Rotarians endorsing the note. We raised $1,600 for one chap, I remember, and that was a lot of money in those days when butchers gave away liver. Most borrowers made good. But one fellow in the then new tire business got into trouble so often we got tired of bailing him out - and so gradually let the business-exchange idea die out. But as we took a personal interest in the success of fellow members, we got to thinking about how he did business. Did he charge enough to get a profit to keep going? Did he cheat'? Was he square with employees? Or did the trouble lie in his competitors? Soon it dawned on us that if we as individual businessmen were to make a go of things, we'd have to clean up crooked practices in our trades. That led to the "every Rotarian an ambassador to his craft" idea. My trade being printing, I helped to start the Ben Franklin Club among my competitors. At first it was a social society, but before long some of us insisted that "the laborer is worthy of his hire" and that we should figure fair costs in our quotations - say, $2 an hour for type composition - and so on. A businessman's first responsibility , we used to say, is to himself - to stay in business. Unless he did that, he couldn't serve his creditors, is employees, or his customers. Other Rotarians - not only in Chicago - picked up such notions, and out of them came the effort to get trade associations to adopt codes of ethics. Nobody says Rotary's Vocational Service of today is selfish, but it all started with the scratch-my-back-and-I'll-scratch-yours idea. I see no more reason to be ashamed of that than for a man being ashamed that once he was a boy. What's important is that we grow up. But if you think back scratching is all we thought of when Rotary was young, you make a mistake the size of a courthouse. Sure, one of the two Objects in our Constitution - written in 1905 and adopted in 1906 - was "The promotion of the business interests of its members." But don't overlook the second: "The promotion of good fellowship and other desiderata ordinarily incident to Social Clubs." To us, both were as natural and normal as having a right and a left hand - as in the case of Paul meeting Silvester. Paul was the friendly sort. He liked the "Good morning, Paul" he used to hear as a boy back in Vermont and missed it. He used to tell how a lawyer friend, Bob Frank, made him hungry for it. Frank had invited Paul - in 1900 I think it was - out for dinner in his suburban home. All the way down the street it was, "Hi, Bob!" It seemed such a good custom Paul got to thinking about ways to develop it in Chicago. So he talked it over with Silvester and the Club was organized in 1905. That's what the official record says. But I distinctly remember one hot Summer day in 1904 that Paul discussed the idea with me, and I printed at least four jobs dated 1904 for the Club. I've had lots of arguments about all this with Charlie Newton, our insurance member of the 1905 class, who is now my neighbor in Los Angeles. I can't convince him because long ago I burned all those old job tickets. Probably even if I could show him the stuff, he'd say the "1904" was a printer's error. Well, what's the difference any way! The American Declaration of Independence wasn't signed on July 4, though we celebrate it on that date. Whether Rotary started in 1904 or 1905 isn't important - except to me. I'd like to win just one argument from Charlie Newton! The official record says on the evening of February 23, 1905, Paul and Silvester dined at Madame Galli's restaurant, then went to the office of Gus Loehr, a mining engineer and promoter, in the old Unity Building where Paul also had hung his shingle. Gus had invited in Hiram Shorey, a merchant tailor. Paul outlined his plans and they agreed to start the club. I was on hand a couple weeks later with the original four at Paul's office for a meeting. The third session was at Silvester Schiele's coal office on State Street near 13th, and to this one came Bill Jensen, a real-estate agent. That in a capsule is the official story. How did we get the name "Rotary"? For a few months I called it the Booster Club, but we were meeting in rotation at members' offices and stores so Paul's suggestion, "Rotary", seemed to fit. But there was another reason for choosing it, and here's the way Paul Harris himself told it in a special Rotary edition of the Chicago Journal of Commerce for February 23, 1922: "The almost forgotten reason," he wrote, "was that it was our plan to elect to membership for one year at a time, making it necessary for each member to stand the test of re-election each year. We thought that such provision would stimulate regularity of attendance, but this plan was never put into effect." The reason it wasn't is also worth recalling because it started the custom of fines. Every member of the Chicago Rotary Club who failed to attend a meeting - with or without excuse - was fined 50 cents. In 1908 we fined a member 50 cents more if he didn't send in a return postcard stating whether he would or would not attend. Fines provided all our income - but remember, a half dollar in those days was half of a real dollar and would buy a good table-d'hote dinner. The scheme worked only fairly well. "Rough House" Chapin (we called him "Rough House" because he was so quiet) had been named Treasurer, succeeding me, and his report on June 20, 1908, showed we had about 175 members and that fines and semi-monthly assessments for the preceding nine months amounted to $533 - with a balance, after allowing for unpaid bills, of $1.84. Paul Harris was President, and, in a letter to members, had this to say: "At the last meeting of the Ways and Means Committee, it was decided, owing to the natural reluctance on the part of his Majesty the American Citizen to pay anything in the nature of a fine, we would do well to call the semi-monthly charge of 50 cents dues instead of a fine." That was done - but the fine idea was still a fine idea for special occasions. If your Club is one that levies a dime when a member addresses another as "Mister", it carried on an old, old tradition because it goes right back to the beginning. Most of us were strangers to one another, and we were in dead earnest about speeding up the process of getting acquainted. It seemed natural to do this by using first names, just as we had as boys back in small towns where most of us had grown up. Fines and first names are just two of' many customs in Rotary today that go back to earliest days in Chicago. When I reminisce, I'm always reminded of the copybook maxim I learned as a boy in a country schoolhouse: "Just as the twig is bent the tree's inclined." More often than not, the Rotary twig was bent by chance. Today we have weekly luncheons with speeches because Charlie Newton once was late. Members had dined here or there at restaurants that night, then assembled at Bill Jensen's real-estate office. When roll was called, Charlie was absent. Pretty soon he came puffing in - very late. His restaurant waiter was slow, he said. He'd missed most of the meeting, so we levied a fine - but Charlie protested. "Anyway," he argued, "why don't all of us have supper together somewhere, then come in a body to the meeting place?" Nobody 'could answer it - so that's what we decided to do, forgetting all about the fine. The plan developed difficulties, however. When we strolled over from a restaurant to E. W. Todd's hay and grain store, for example, we had to perch around on bales of hay. Sometimes rain or snow made the walking bad. Then one night Al White, who was in the folding organ business, came up with a bright idea. "We like Brevoort Hotel food," he said, "so let's eat there regularly. The management 'will give us a room where we can park hats and coats on the bed.." Well, it wasn't long before we were meeting in the bedroom - instead of some store or office. But sitting two deep on beds and tables was about as unsatisfactory as on bales of hay. So we moved over to the old Sherman House, where we got a large bedroom with the bed replaced by chairs. Before long we got the management to serve us in the room. We were meeting twice a month at night. The shift to weekly meals at noon came in 1907. Paul as President was having weekly luncheons with his Executive Committee (later Ways and Means) at Vogelsang's Restaurant at Madison and LaSalle. Any member could attend, so these luncheons became popular. Then someone - and Paul probably had planned it that way all the time! - proposed that these weekly sessions be regular Club meetings. The idea caught on. And that's the way the weekly luncheon idea evolved - all because Charlie Newton was quick with an alibi for being late! Other Rotary customs developed just as simply and naturally - oaks that grew from pretty small acorns. Take Community Service. If you know your Rotary history, you've read it started with a campaign of Chicago Rotarians in 1907 to install comfort stations in the City Hall. But a year before that, "Doc" C. W. Hawley, our eye man, told us about the plight of a country doctor in near-by LaGrange whose horse had died. So we dug up $150 to buy another - then forgot all about the incident. I can't even remember the physician's name. Old No.1 wasn't the streamlined thing it is now. I guess we were pretty careless about details. When a fellow changed his business to another not represented in the Club, he carried his membership over without ado. Sometimes he'd simply tell me, and as printer I would make the correction in the roster. It took serious trouble in one case for us to realize we had to be more businesslike. After that, the Club itself authorized all changes in classifications - a practice now written into the By-Laws of every Rotary Club of the world. I was printing postcard announcements and letters of meetings in those days, and when there was space I'd slip in an item about some member. The fellows liked it, so at "Red" Ramsay's suggestion we, started a regular publication. It was called the Rotary Yell until "Rough House" Chapin, who always was a great hand at punning and other tricks with words, proposed that we use Rotary backward, but start it off with a "G" for a reason I've forgotten. That made Gyrator. The Gyrator is still published by the Rotary Club of Chicago and is the great granddaddy of the thousands of little papers issued by Rotary and other service clubs. Meetings often were pretty dull, that first year or two. Most of the chatter at first was about how much business this or that person got or gave to some other Rotarian. Then Silvester Schiele, at Paul Harris' urging, gave a talk about his coal business - the first of countless Rotary "my vocation" talks. Silvester later came up with another idea; that to three meetings a year we invite the ladies. I don't recall a dissenting vote, which may have been due to the fact that most members, like Silvester and Paul, were then bachelors. Liquid refreshments - our 50 cent meals would include wine or claret livened sessions but created a problem. Some of the boys would tread the brass rail before sessions and, feeling pretty good, would speak up at the wrong time. The President would rap the gavel and shout, "0rder, order!" It was funny for a time or two, then we decided if we were going to carry on in an orderly way, we'd have to taboo liquor at meals. That rule has become general in Rotary Clubs throughout the United States, at least. Once we were having an especially dull meeting. I remember it well. We were still meeting in our double bedroom at the Sherman, and I for one had got pretty tired of just chewing the rag. "Gosh, fellows," I finally said, "let's sing!" By that time I was standing on my chair, waving my arms, and swinging into "Let Me Call You Sweetheart". Maybe it was "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny" or my favorite "My Hero" from The Chocolate Soldier or "Hail, Hail, the Gang's All Here!" I don't remember. Anyway, I let out my baritone, Paul Harris added his neat tenor, and we were off into barbershop harmony. That's the simple, unplanned way it all happened. I get kind of embarrassed when I'm introduced to Rotary audiences as "the father of Rotary singing," because it all happened so naturally. I came from a "singing Methodist" family. Each morning and every night my father would read a chapter from the Bible and then, before a prayer, we'd sing a hymn. So I really don't deserve any special credit. But singing did catch on. The next time we met the gang said, "Come on, Harry, let's try another!" That kept up regularly, so I printed a sheet giving words of songs we liked best. I wonder if a body has a copy! today. When our print shop moved from Monroe Street to Wacker Drive, I threw away old job tickets, so I don't have even a proof of it or of the later song books I used to give to new Rotary Clubs. But how was I to know I was "making history"? Imagine my surprise one day when I read in The Rotarian in an article by Sigmund Spaeth, a real musician, this: "And here I would bear testimony that when that Chicago printer, Harry L. Ruggles, got Rotary Club No.1 to singing . . . he put in his debt everybody who enjoys communing singing. For it was Rotary singing that gave impetus to the vogue for community singing which started in prewar (World War I) days and still is running strong. Talk about having fame thrust upon you! Paul Harris told me a number of years ago that at first he had doubts about singing in Rotary Clubs. But he was soon converted and in his This Rotarian Age - page 42, if you're interested - he says some pretty nice things about it. He even quotes Plato and Damon and goes on to say the only thing about "the early Christians that baffled Pliny's understanding was their psalm singing." Some Rotarians in certain parts of the world are as puzzled about Rotary singing. A French Rotarian, for example, once said he never knew before of sober men singing in the daytime. Yet I'm told that quite a few overseas Rotary Clubs are now singing Clubs. Singing is responsible for another rather common Rotary tradition, dating back to about 1906 in the Chicago Rotary Club. An out-of-town speaker one day started a smutty story. I knew what was coming - after all, I once was a printer's devil - so I jumped to my feet and started singing one of our favorites. Others joined and we just drowned out the speaker. He was embarrassed - in fact, pretty sore about it. Of course I apologized. But the Club seemed to think I had done all right and agreed that our meetings ought to be the sort that a lady could attend without blushing. That feeling hardened into an unwritten rule that has since become a general Rotary tradition. Yes, Old No. 1 learned the slow and sometimes the hard way. I remember how we used to pass out honorary memberships right and left, as an easy way of "paying" for a speaker... Once after we had done this for a lobster man from Nova Scotia, we concluded that honorary membership should be a real honor - so put the brakes on. Passing resolutions was easy, too. We had hardly opened our eyes as a Club before we tabooed religion and politics in Club discussions, but we didn't realize what dynamite there was in resolutions till in a burst of enthusiasm after a speech we resolved that lumber was a better building material than brick. And did the bricks then come our way! Right then and there we stopped such resolutions and I guess the Rotary International warning of today that Clubs take no "corporate action" goes right back to that fumble. Yes, Rotary in those days just sort of "growed up like Topsy." We "cut and fit" action and rules as problems came up. None of us - even Paul Harris - dreamed of what Rotary might and has become. I often think of what my father used to say about God working in mysterious ways His wonders to perform. So I am both happy and humble as I recall my little part. I've seen Rotary develop from five men into an organization of 350,000 members with 7,400 Clubs in 83 countries - more international than the United Nations! In 1955 Rotary will celebrate its 50th birthday in Chicago where it was born. God willing, Josephine and I'll be there. Maybe (?) I will once again lift my hands and say, "Let's sing!" From - The Rotarian, February 1952. [Reprinted by permission 2004]

|

| Copyright© Daniel W. Mooers |

Rotaryģ and Rotary Internationalģ are registered trademarks of Rotary International Webmaster: dwm@mooers-law.com |